Water cycle, also called hydrologic cycle, cycle that involves the continuous circulation of water in the Earth-atmosphere system.

Of the many processes involved in the water cycle, the most important are :

- evaporation,

- transpiration,

- condensation,

- precipitation

- runoff.

Although the total amount of water within the cycle remains essentially constant, its distribution among the various processes is continually changing.

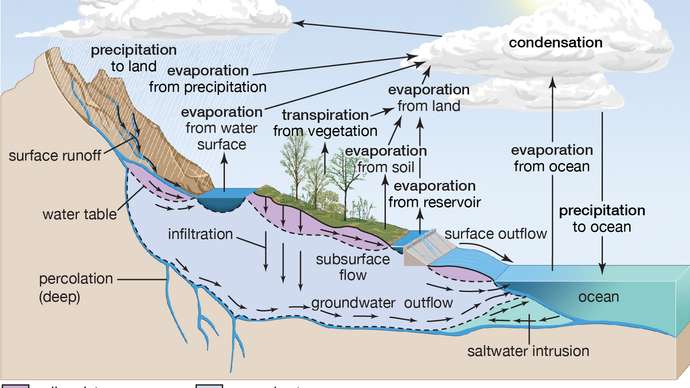

Evaporation, one of the major processes in the cycle, is the transfer of water from the surface of the Earth to the atmosphere. By evaporation, water in the liquid state is transferred to the gaseous, or vapour, state. This transfer occurs when some molecules in a water mass have attained sufficient kinetic energy to eject themselves from the water surface. The main factors affecting evaporation are temperature, humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation. The direct measurement of evaporation, though desirable, is difficult and possible only at point locations. The principal source of water vapour is the oceans, but evaporation also occurs in soils, snow, and ice. Evaporation from snow and ice, the direct conversion from solid to vapour, is known as sublimation. Transpiration is the evaporation of water through minute pores, or stomata, in the leaves of plants. For practical purposes, transpiration and the evaporation from all water, soils, snow, ice, vegetation, and other surfaces are lumped together and called evapotranspiration, or total evaporation.

Water vapour is the primary form of atmospheric moisture. Although its storage in the atmosphere is comparatively small, water vapour is extremely important in forming the moisture supply for dew, frost, fog, clouds, and precipitation. Practically all water vapour in the atmosphere is confined to the troposphere (the region below 6 to 8 miles [10 to 13 km] altitude).

Precipitation that falls to the Earth is distributed in four main ways: some is returned to the atmosphere by evaporation, some may be intercepted by vegetation and then evaporated from the surface of leaves, some percolates into the soil by infiltration, and the remainder flows directly as surface runoff into the sea. Some of the infiltrated precipitation may later percolate into streams as groundwater runoff. Direct measurement of runoff is made by stream gauges and plotted against time on hydrographs.

Most groundwater is derived from precipitation that has percolated through the soil. Groundwater flow rates, compared with those of surface water, are very slow and variable, ranging from a few millimetres to a few metres a day. Groundwater movement is studied by tracer techniques and remote sensing.

Ice also plays a role in the water cycle. Ice and snow on the Earth’s surface occur in various forms such as frost, sea ice, and glacier ice. When soil moisture freezes, ice also occurs beneath the Earth’s surface, forming permafrost in tundra climates. About 18,000 years ago glaciers and ice caps covered approximately one-third of the Earth’s land surface. Today about 12 percent of the land surface remains covered by ice masses.

General nature of the cycle

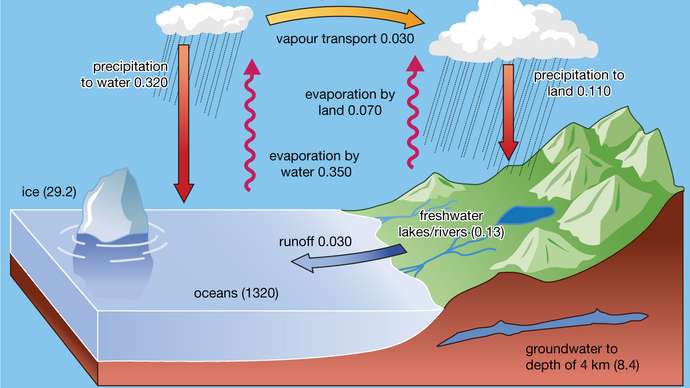

The present-day water cycle at Earth’s surface is made up of several parts. Some 496,000 cubic km (about 119,000 cubic miles) of water evaporates from the land and ocean surface annually, remaining for about 10 days in the atmosphere before falling as rain or snow. The amount of solar radiation necessary to evaporate this water is half of the total solar radiation received at Earth’s surface. About one-third of the precipitation falling on land runs off to the oceans primarily in rivers, while direct groundwater discharge to the oceans accounts for only about 0.6 percent of the total discharge. A small amount of precipitation is temporarily stored in the waters of rivers and lakes. The remaining precipitation over land, 73,000 cubic km (17,500 cubic miles) per year, returns to the atmosphere by evaporation. Over the oceans, evaporation exceeds precipitation, and the net difference represents transport of water vapour over land, where it precipitates as rain or snow and returns to the oceans as river runoff and direct groundwater discharge.

The various reservoirs in the water cycle have different water residence times. Residence time is defined as the amount of water in a reservoir divided by either the rate of addition of water to the reservoir or the rate of loss from it. The oceans have a water residence time of 3,000 to 3,230 years; this long residence time reflects the large amount of water in the oceans. In the atmosphere the residence time of water vapour relative to total evaporation is only about 10 days. Lakes, rivers, ice, and groundwaters have residence times lying between these two extremes and are highly variable.

There is considerable variation in evaporation and precipitation over the globe. In order for precipitation to occur, there must be sufficient atmospheric water vapour and enough rising air to carry the vapour to an altitude where it can condense and precipitate. Precipitation and evaporation vary with latitude and their relation to the global wind belts. The trade winds, for example, are initially cool, but they warm up as they blow toward the Equator. These winds pick up moisture from the ocean, increasing ocean surface salinity and causing seawater at the surface to sink. When the trade winds reach the Equator, they rise, and the water vapour in them condenses and forms clouds. Net precipitation is high near the Equator and also in the belts of the prevailing westerlies, where there is frequent storm activity. Evaporation exceeds precipitation in the subtropics, where the air is stable, and near the poles, where the air is both stable and has a low water vapour content because of the cold. The Greenland Ice Sheet and the Antarctic Ice Sheet formed because the very low evaporation rates at the poles resulted in precipitation exceeding evaporation in these local regions.

Stop water from going into the drain,

Make a collective effort & catch the rain!

Vardhman Envirotech,

India’s Passionate Rainwater Company