Temperature gauges in the Pacific Ocean point to an El Niño developing this year. Despite the warnings, many of us overlook the phenomenon that has reshaped India time and again. The El Niño or ‘Little Boy’ (referring to Baby Jesus), is so named because Peruvian fisherman noticed their fishing catch fall around Christmas every few years. By the 1960s, scientists discovered that fish harvest fell because of a rise in ocean temperatures off the Peruvian coast — a rise that was part of vast Pacific Ocean-air temperature see-saw between Australia and Peru. Every few years, this see-saw would bring rain to Australasia, and when it swung the other way, rain to the Peruvian coast. Moreover, whenever Peruvian fisherman saw poor fishing, the Indian monsoon faltered. While scientists have discovered more such ocean-air see-saws that affect the Indian monsoon, the El Niño’s influence, though nuanced, remains strong. Every major drought that has struck India has been during an El Niño — and the truly massive El Niños have transformed India.

Consider the 1877 El Niño. India was then the crown jewel of the British Empire, and its wealth was being systematically and ruthlessly transferred to England. Much of India’s forests had been cleared and a fixed, payable-in-cash tax had coerced farmers to shift from climate-resilient millets to cash crops like indigo, opium and cotton, unsuited to India’s rainfall and inedible in a drought. By 1876, a powerful El Niño was forming, and India’s rains began to fail. Soon, millions left their withered fields in the Madras Presidency to beg for food. British tight-fistedness in granting relief — historian Mike Davis said the calories offered by the relief camps at the height of the famine were less than those given in Nazi concentration camps — caused public outrage to erupt. Protesting the unfairness of the conditions, 102,000 people refused to attend relief work (which, given the lack of alternatives, was tantamount to accepting a death sentence). The British administration termed this strike ‘passive resistance’ because there was little violence — a term that would come to define India’s independence movement. Over five million Indians died in that famine, leaving the country seething in resentment. This anger fuelled organisations like the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha and the Arya Samaj, whose leaders like Ranade, and later, Tilak and Gokhale, played key roles in the country’s Independence struggle. The famine also unleashed a wave of dam-and-canal building in a desire to control water.

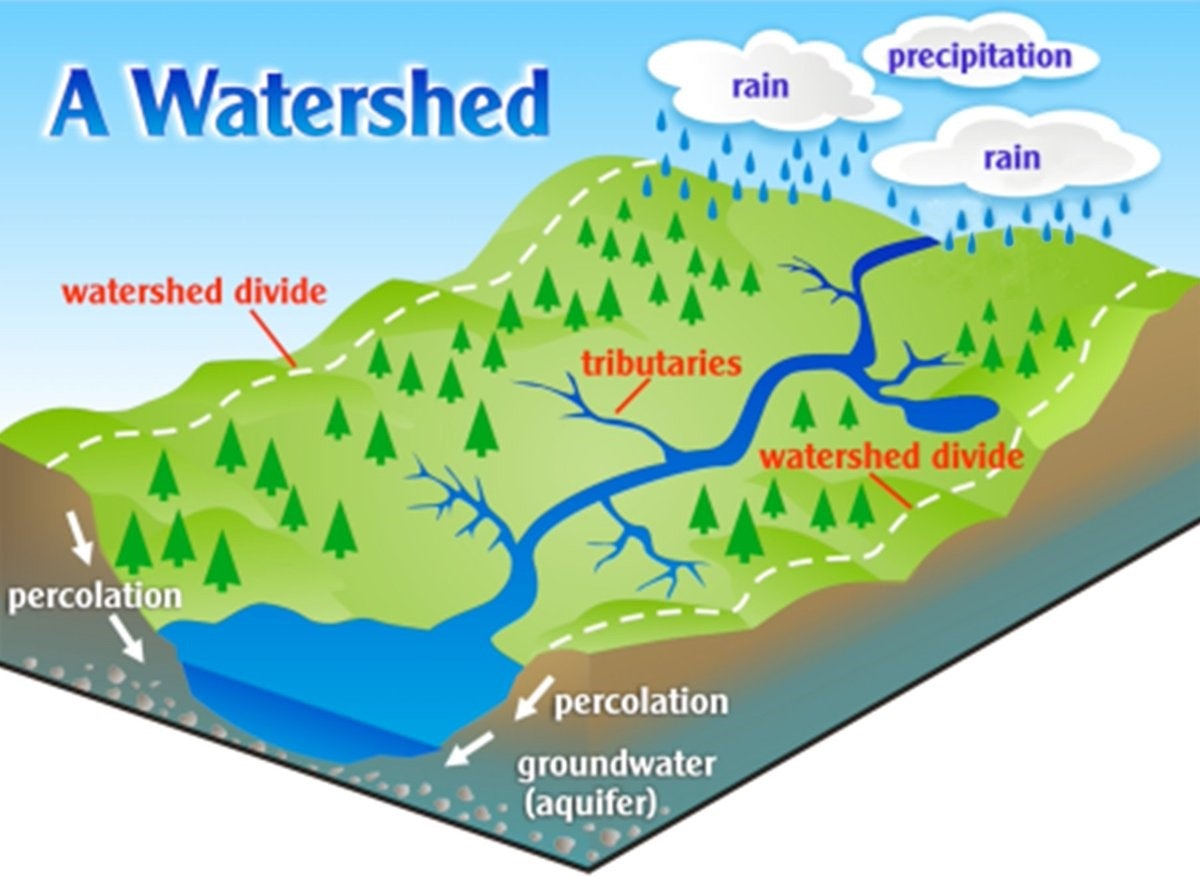

Photo courtesy: rcrcd.org

Fast-forward to 1965. While India had shed its imperialistic yoke, Nehru believed that India could never be truly free as long as it lacked food security. In the 1950s and ’60s, India had become addicted to cheap American wheat. It seemed a sweet deal: pay for cheap grain in Indian rupees and save dollars for industrialisation. But when the El Niño struck, India’s grain production suffered, particularly in Bihar where the situation became dire. Early in 1966, a new prime minister, Indira Gandhi, confronted a nation that had just emerged from a war and was staring at famine. Importantly, her party was staring at electoral defeat in Bihar’s elections. Mrs Gandhi visited Washington in March 1966 to plead for aid, which the American President promised to provide. But then, India dared to condemn the American bombing of Vietnam. Pissed, America kept India on a short leash, and released its grain, tonne-by-precious-tonne, to ensure India behaved and made policy changes. India devalued its currency by 57% in June 1966, and opened up some of its economy to private forces. Smarting but hungry, India vowed to become food secure. In the background, the Green Revolution was just getting started, sparking a borewell revolution in dry Punjab and Haryana, making that dry land spew forth unbelievable quantities of grain. The mid-1960s saw the creation of the Food Corporation of India to buy grain and the Minimum Support Price to motivate farmers to make more grain. Within decades, India became food secure and truly independent. Ask yourself, could India have been able to buy Russian oil so easily today if it depended on European grain to feed itself?

Photo courtesy: National Ocean Services

Let us move ahead to a monster El Niño and the back-to-back droughts of 2015-16. Surprisingly, India has shown resilience. Have we conquered the El Niño? Hardly. Our groundwater reserves have bought us climate wiggle room. But when those reserves begin to sputter, especially in India’s dry breadbaskets, the El Niño will be waiting. Even in 2015-16, India saw thousands of heat wave deaths, devastating floods, Day Zero in cities, power plants shut down by lack of water and farmer suicides spike in Maharashtra and Karnataka. When groundwater runs out, add famine to this list. Metaphorically, it’s only when the tide recedes do we see who has been swimming naked. El Niños, by pulling the tide back and exposing vulnerabilities, force change. What will it show us this time?

Vardhman Envirotech

India’s Passionate rainwater company

Article written by Mradula Ramesh is the author of ‘Watershed: How We Destroyed India’s Water and How We Can Save It’ and publish in TOI – 07/ MAY /2023. All credits goes to her.

We would like to spread this for the benefit of fellow Indians.